Tokyo Park Inspired Washington’s Cherry Trees

“No other flower in all the world is so beloved, so exalted, so worshipped, as sakura-no-hana, the cherry-blossom of Japan.”

— Eliza Scidmore, The Century Magazine, May 1910

It’s now blooming season in Washington. That means cherry tree fever along the Tidal Basin in Potomac Park.

The display offers our own “Mukojima on the Potomac,” as Eliza Scidmore envisioned it more than a century ago. She got the idea from the popular cherry tree park in Tokyo known by that name.

Bruce and I made our annual pilgrimage to see the cherry blossoms on Saturday morning, under a clear but very chilly sky. We’ve learned it’s best to go very early, when tourists are still waking up or at breakfast. We can usually zip into town and find off-street parking not too far from the National Mall.

Happy Birthday

Today is the official birthday of the trees. The first ones, from a shipment of 3,000 donated by Japan, were planted on March 27, 1912.

Eliza Scidmore started pushing the idea of cherry trees in Potomac Park during her travels to Japan in the 1880s. She loved the ritual known as hanami, or cherry-tree viewing. The tradition dates back centuries, when all the Japanese turned out to admire the blossoms and mingle beneath the branches.

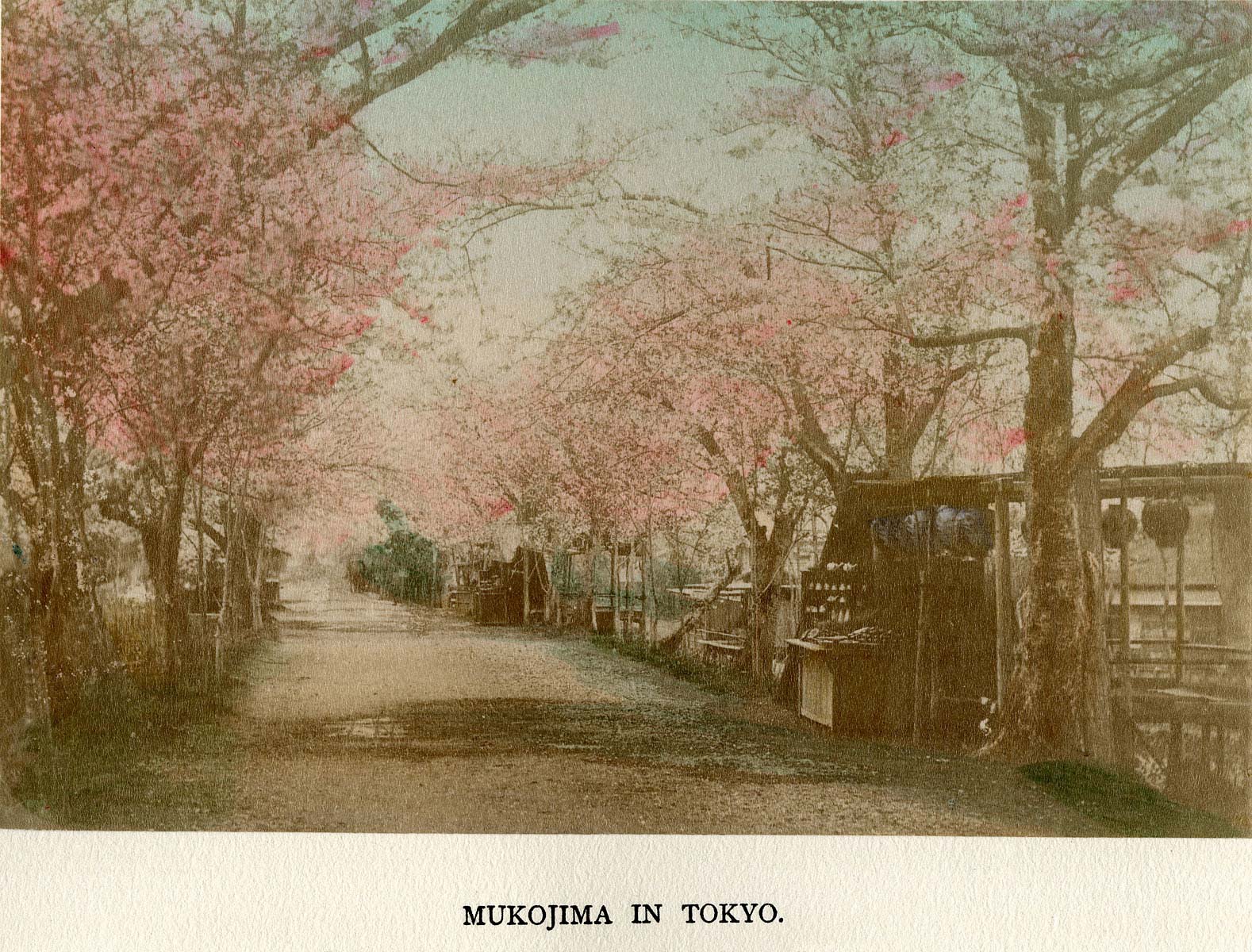

Mukojima, where cherry trees stretched for a mile along the Sumida River in Tokyo, offered a major source of inspiration .

Below are some photos of what Mukojima looked like around the time Eliza went there. See more great images at this website featuring vintage postcards of old Tokyo.

Ramble under the cherry trees, by Takashima , 1897

Cherry trees at Mukojima, from Frank Brinkley’s 10-volume series “Japan”

Source of Inspiration

Mukojima served as a royal hunting grounds during Japan’s Tokugawa era. The area was a short ferry ride across the river from a temple district. After one of the shoguns planted an orchard of flowering cherries, common folk went every spring to admire the blooms.

The country’s literati visited Mukojima for inspiration, and the wealthy elite built retreats nearby. But the site also remained popular with the public.

Scidmore described Mukojima as something of a “people’s park” that drew hordes of Japanese from all walks of life. They picnicked under the trees and drank saké; pinned poems to the branches and let the tissue-thin strips of paper blow away in the wind. Entertainers and vendors gave it a carnival-like atmosphere. She loved the joviality and spirit of goodwill that hanami seemed to bring out in people.

I had a chance to visit Mukojima during a research trip to Japan in 2013. The setting is certainly more modern, but the spirit hasn’t changed.

Today, the crowds that circle the Tidal Basin in Washington are enacting that same ritual of hanami. Photos of the trees with the Washington Monument or Jefferson Memorial in the background may be the most-loved images of the nation’s capital.

It’s the very experience Eliza Scidmore wanted to re-create in Washington.

Hardy Survivors

It took three decades for Scidmore to see her dream become a reality, thanks to the support of First Lady Helen Taft.

Then in her 50s, Scidmore was one of only three special guests to witness the small private ceremony when Mrs. Taft planted the first cherry tree by the Tidal Basin. The Japanese ambassador’s wife, Madame Iwa Chinda, planted the second one.

Site of two earliest cherry trees from Japan planted by the Tidal Basin in 1912, with Washington Monument in the background (Photo: Diana Parsell)

Remarkably, those first two trees are still standing. They are west of the John Paul Jones statue, just south of a Japanese lantern donated later by Japan. A plaque marks the historic event.

The life of cherry trees is typically about 40 years, so those two are real survivors.

Gnarled and misshapen from lost limbs, they gallantly hang on, thanks to the loving attention of the National Park Service.

Many of the original 3,000 trees have been replaced over the years. But another hardy survivor stands on the grounds of the Library of Congress, where I go often to do research for my biography of Eliza Scidmore.